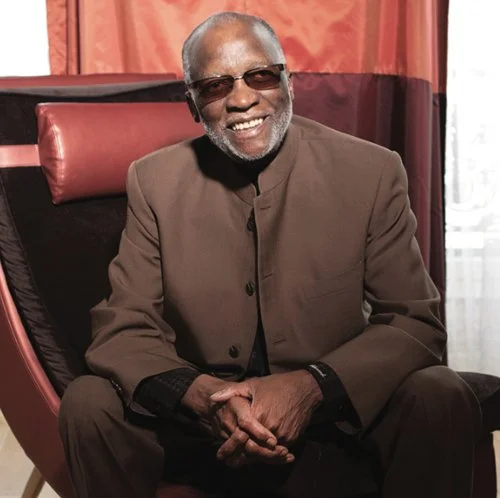

AHMAD JAMAL

NEA Jazz Master

NY Times Article:

A pair of Ahmad Jamal live albums capture innovator his prime.

Ahmad Jamal’s

Piano Solo on ‘Saturday Morning (Reprise)’

Downbeat Review:

“10,000 stars” Spike Wilner said of Ahmad Jamal.

BALLADES

4.5

★

★

★

★✭

DOWNBEAT Magazine

BEST ALBUM 2019 4.5 stars

DownBeat Review:

AHMAD JAMAL

"Ballades"

The new release out NOW

KCRW Review

Ahmad Jamal: Ballades

Solo Piano

New York City Jazz Record Review

Ahmad Jamal l BALLADES

by Stuart Broomer

Pianist Ahmad Jamal, who turns 90 this month, has worked for most of the past 70 years as the leader of very distinctive trios, first with guitar and bass, then bass and drums, sometimes supplementing them with percussion or collaborating with a horn soloist.

His distinctive use of vamps and ostinatos has made him both influential (on musicians like Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Keith Jarrett) and a bête noire (literal meaning intended) for a certain kind of critic who can’t understand jazz that’s genuinely popular or genuinely original. Jamal may have also suffered for achieving a certain perfection in his ‘50s trio with bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernel Fournier.

This solo recording dates from 2017, when Jamal was already 87, but there’s nothing to suggest decline in his skills as he explores a program including personal standbys, enchanted ballads and scattered originals, occasionally with his regular bassist James Cammack joining in. The music can pass for sweetly decorative, but it’s also music by a man who would open a jazz club, in Chicago circa 1960, which didn’t serve alcohol and was called the Alhambra for that Andalusian encyclopedia of geometric pattern and infinite reflection, a temple of perfectly chiseled text. Sometimes the music doesn’t seem strong on shape or drama, but Jamal is a master of a dense chromaticism overlaid on beautiful tunes and he shapes adjoining, shifting segments by drawing from that chromatic wealth, moving from overlays of exotic modes suddenly to reveal the original composer’s particular and perfect harmonic sequence, as in “Poinciana”, a tune with which Jamal has undoubtedly spent vastly more time than its composer, Nat Simon, who jotted it down on a restaurant table cloth and seems to have adapted it from a Cuban folk song. The same gifts are applied to repertoire like “So Rare” (Jimmy Dorsey), “I Should Care” (Axel Stordahl-Paul Weston-Sammy Cahn), “What’s New” (Bob Haggart-Johnny Burke), “Spring Is Here” (Richard Rodgers-Lorenz Hart) and Johnny Mandel’s “Emily”, a song so beautiful that Jamal barely deigns to exploit its melody.

There’s a sense of reverie, of reflection, everywhere here. A well-known moment in Ken Burns’ Jazz is when Duke Ellington, being interviewed at a piano and playing sporadically, remarks, “This isn’t piano. This is dreaming.” That’s precisely what Jamal offers here.

BALLADES

4

★

★

★

★

Jazz Journal

AHMAD JAMAL

on having a spiritual anchor, Jimmy Heath

& the world beyond the piano

SFJazz kicks new season off with Ahmad Jamal

and the promise of a vibrant future

Ahmad Jamal opens SFJAZZ season

Top Bay Area Concert Picks of Week (Sept. 5-11)

Highlights of SFjazz 2019

AHMAD JAMAL

Legendary jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal to release new 2xLP, Ballades

VF

Ahmad Jamal, parcours d’un pianiste à l’écart des standards de jazz

Musiques Portrait

Ahmad Jamal's Pianism Remains Wondrous

Chicago Tribune

Essential Music

“Featured fan Review!

Ahmad Jamal in St Louis, 3/30/19, by Suzanne Rhodenbaugh:

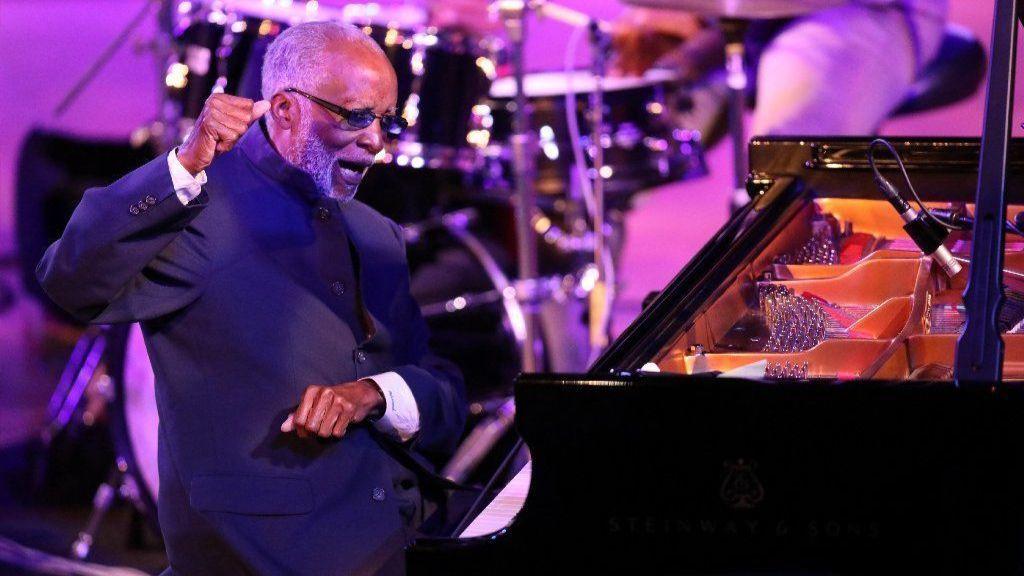

”Jamal! — Masterful. As soon as he touches the piano you know he’s the master and that’s it. He’s a small man, almost delicate, and a handsome man, and I love the way he moves when he’s playing. He sways his upper body part of the time, almost like a slow shiver, and sometimes raises his right shoulder, which is somehow enthralling, and when there’s a beat he alternates the foot keeping the beat.

He is generous with his fellow musicians — a base player, a drummer, and a guy who plays kettle drums (or tumbadoras?), maracas, (sp?), bells, etc. He sometimes points to one of them when he wants one to come in, and/or when he wants them to take the featured role. At one point, when the drummer was holding forth a long time, he turned around from the piano, folded his arms and grinned, as if to say, “Do I need to be here?”

We’ve seen other musicians who were old, for whom we had to make allowances -... . But no allowance need be made for Ahmad Jamal. As far as I can tell, he’s still a powerhouse, but with the subtlety that comes from being a long master. When he first sat down at the piano, by the way, he noted that he’d first played in St. Louis 71 years ago. ...

He strikes me as someone who would be kind and generous in daily life. He knows his skill and value, but is not a showboat. And he seems so pleased when the audience responds. All in all, a class act!””